Introduction and Background

Ambient vital sign monitoring refers to contactless, unobtrusive tracking of physiological signals (like respiration and heart rate) using devices embedded in the environment rather than on the body. Recent years have seen rapid progress in using radio wave-based technologies (low-power microwaves, Wi-Fi-like signals, millimeter-wave radar, etc.) to monitor subtle body motions caused by breathing and heartbeats. These systems exploit the fact that each breath or heartbeat causes minute movements of the chest and body surface, which in turn modulate reflected radio signals. By analyzing these reflections with advanced signal processing and AI, one can continuously measure vital signs without any wires or wearables on the person. This contactless approach offers important benefits: it eliminates discomfort and skin irritation from electrodes (critical for infants or burn patients), preserves mobility and sleep quality, and reduces infection risk by minimizing physical contact. During the COVID-19 pandemic, interest in such remote monitoring surged, since it allows tracking patients’ breathing and health status from a distance. Moreover, continuous at-home monitoring can reveal early signs of health deterioration that might be missed by infrequent vital checks in clinical settings. Researchers are now leveraging these radio-based sensors to detect critical events like suspected cardiac arrest or respiratory failure (by sensing absence of motion/breathing), as well as more subtle changes such as rising respiratory rate or irregular heart rhythms that precede acute medical events. Below, we review key technologies and studies in this field – including pioneering work by Dina Katabi’s group (e.g. WiTrack, Vital-Radio, Emerald) – and highlight recent peer-reviewed research (primarily 2020–2025) on clinical applications from home to hospital.

Radio Wave Technologies for Contactless Vital Signs

Early work demonstrated that radio signals can “see” human motion through walls, enabling novel sensing systems. For example, Katabi’s team at MIT introduced WiTrack in 2013–2014, a device that tracked a person’s 3D movement from radio reflections off their body. Building on this, they asked if tiny motions – like chest motions from breathing or even skin vibrations from heartbeats – could also be detected. This led to Vital-Radio, a wireless sensing technology that accurately monitors breathing and heart rate with no body contact. Vital-Radio transmits a low-power signal (comparable to Wi-Fi) and processes the reflections to extract vital signs, even at a distance or through obstacles. In a 2015 study (Adib et al.), Vital-Radio was shown to track multiple people’s respiration and pulse with about 99% median accuracy at up to 8 meters away, even from an adjacent room. This was a foundation for truly ambient, room-scale vital sign monitoring. The system can pick up minute chest motions from breathing and even the subtle “cardiac micro-oscillations” on the body’s surface caused by each heartbeat.

How it works: These radio-frequency (RF) sensing systems typically emit a very low-power microwave/ultrawideband signal and listen for its echo from the environment. Any movement – down to sub-millimeter chest expansions – will slightly change the timing or phase of the reflected waves. By isolating the periodic signals corresponding to breathing (~0.2–0.3 Hz in adults) or heartbeats (~1 Hz), the device algorithm can derive respiration rate (RR) and heart rate (HR). Advanced models use techniques like frequency-modulated continuous wave (FMCW) radar or Doppler radars to measure distance changes precisely, or they leverage channel state information in Wi-Fi signals. Modern approaches also apply machine learning to untangle the weak heartbeat signal from larger body motions and noise. For instance, algorithms based on variational mode decomposition and harmonic analysis have been developed to suppress the confounding effects of gross body movement and respiration on the heartbeat signal. As a result, today’s RF sensors can achieve high fidelity – often within a few beats per minute error for heart rate – in realistic environments with people going about their lives.

Key Innovations and Systems in the Past 5 Years

Dina Katabi’s Contributions (WiTrack, Vital-Radio, Emerald)

Professor Dina Katabi and her students have been leaders in this field, creating a series of innovations: from WiTrack’s through-wall tracking to Vital-Radio’s contactless vitals, and eventually Emerald, a polished device for real-world healthcare. Emerald is essentially a “smart Wi-Fi box” that uses AI to continuously monitor a person’s breathing, heartbeat, sleep, and movements 24/7 with no wires or wearables. The device is about the size of a router and emits wireless signals 1,000 times weaker than Wi-Fi, analyzing their reflections in the background. Katabi’s team spun out Emerald Innovations in 2013 to commercialize this technology, and by 2020 Emerald units had been deployed in over 200 locations (hospitals, homes, assisted living facilities).

The system uses machine learning on the RF reflections to extract a rich set of digital biomarkers – not only respiration and heart rate, but also sleep stages, time spent walking, gait speed, and even metrics related to mood or neurological health. In other words, the Emerald device can passively build a holistic picture of a person’s health at home.

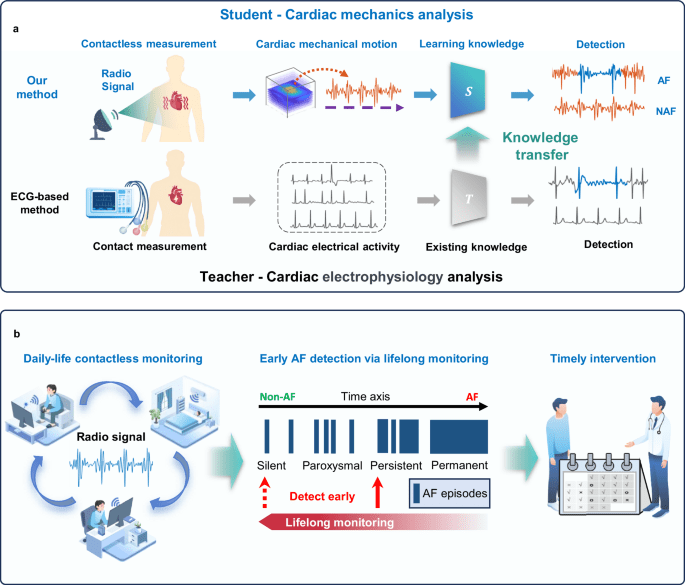

Crucially, studies have demonstrated Emerald’s ability to monitor patients in both home and clinical contexts. Figure below illustrates how such a radio-based system works for cardiac monitoring and early detection of arrhythmias, as developed by other researchers (more on this in a later section).

One of Katabi’s notable deployments was for COVID-19 remote monitoring. In 2020, an Emerald unit was installed in an assisted-living resident’s room to track his illness progression. The system continuously measured his respiratory rate, sleep quality, and walking speed as he recovered from COVID. Doctors observed that his breathing rate dropped from 23 to 18 breaths/min over time (returning to normal baseline), his sleep improved, and he ambulated faster as health returned. This real-world case highlighted how a contactless monitor could let clinicians track patient recovery or deterioration without risking exposure. More generally, Katabi’s group demonstrated that such sensors can serve as an early-warning system: in a 2021 study, they continuously monitored three older adults in an assisted living facility through acute COVID-19 illness and recovery (3 months). The Emerald sensor captured 4,358 hours of respiration data and 294 nights of sleep, revealing distinctive respiratory patterns. Notably, the symptomatic patients had elevated overnight respiration rates (RR) compared to baseline, whereas an asymptomatic COVID-positive patient’s RR remained normal. In one case, the system detected an unusually high respiratory rate in the days prior to the patient’s hospitalization, flagging the deterioration early. This study by Zhang et al. (2021) provides a proof-of-concept that passive radio sensors can longitudinally track illness trajectories (respiratory and behavioral) and may alert clinicians to worsening conditions (e.g. escalating RR, poor sleep) in real time.

Beyond acute illness, the Katabi lab has applied nocturnal RF monitoring to chronic diseases. In 2022, they published a paper in Nature Medicine showing that Parkinson’s disease (PD) can be detected and assessed via breathing patterns during sleep – all with a touchless RF sensor placed in the bedroom. By training an AI on overnight breathing signals from 7,671 individuals, their model could identify PD with an AUC of 0.90 and even predict disease severity (motor symptom scores) with high correlation (R = 0.94). Impressively, the system works at home: it uses radio waves bouncing off the patient’s body to extract breathing without any wearable, enabling at-home PD assessment in a fully passive manner. This illustrates the broad potential of ambient vital sign monitors – extending into neurological and sleep health.

mmWave Radar Systems for Heart and Respiration Monitoring

Parallel to Wi-Fi-based systems like Emerald, other groups have advanced millimeter-wave radar for vital signs. Short-range 60–77 GHz radars can detect even smaller motions due to their high frequency. In late 2024, Zhang et al. reported a 60–64 GHz RF sensing system capable of long-term heart rate variability (HRV) monitoring with clinical-grade accuracy. Importantly, they tackled one of the hardest challenges: separating the tiny heartbeat-induced motions from the much larger respiration motion in the chest signal. By identifying frequency bands in the radar echoes where heartbeat harmonics dominate (beyond the usual 1 Hz fundamental), they could isolate heart motion despite the “orders-of-magnitude larger” breathing interference. In tests, their contactless system’s HRV measurements matched a gold-standard 12-lead ECG system, yet required no electrodes. They demonstrated this in 6,222 outpatient recordings as well as long-term home sleep monitoring (random nights over months and a continuous 21-night trial). The RF sensor successfully detected different heartbeat abnormalities such as tachycardia and bradycardia with about 83.4% classification accuracy, outperforming prior wireless methods. This work suggests a contactless radar can continuously watch for arrhythmias or heart-rate anomalies across thousands of patients, paving the way for proactive cardiac care.

A follow-up study in 2025 pushed further into specific arrhythmia detection. Researchers developed an AI-enabled radar system for atrial fibrillation (AF), the most common pathological arrhythmia. AF often occurs intermittently and asymptomatically in early stages, making continuous home monitoring appealing for early diagnosis. The team’s solution used a millimeter-wave radar to capture the mechanical pattern of the heartbeat and an AI that learned to recognize AF by “knowledge transfer” from ECG databases. In essence, the radar (as a “student”) measures chest wall motions, and the AI was guided by ECG-based AF knowledge (“teacher”) to interpret those motions. The results are striking: in a test on 6,258 outpatient visitors, the contactless system detected AF with 84.4% sensitivity and 99.5% specificity, approaching the accuracy of clinical ECG. In a real-world pilot, the system was used for proactive daily-life monitoring and it successfully caught AF episodes in 2 out of 27 people before they had been clinically diagnosed. This demonstrates the power of continuous ambient monitoring – potentially catching silent AF and allowing early intervention (e.g. starting anticoagulants to prevent stroke) before a catastrophic event. The authors emphasize this could enable lifelong, seamless screening for AF at home, instead of sporadic clinic ECGs. Notably, both the HRV and AF studies achieved large-scale validation (thousands of subjects) and underline that RF sensors can rival medical devices in accuracy. They also hint at future possibilities: one can imagine a home radar that alerts if someone’s heart enters a dangerous arrhythmia or if their HRV indicates stress or illness.

Smart Environments and Consumer Devices

While the above systems are specialized prototypes, similar technology is also being woven into everyday environments. Researchers at the University of Waterloo, for example, have explored integrating radar sensors into furniture. In 2025, Gharamohammadi et al. demonstrated a “smart chair” with built-in mmWave radar that can measure the user’s cardiac waveform and heart rhythm while they sit. The radar was mounted behind the seat back, and algorithms extracted the mechanical pattern of the heartbeat – finding a characteristic “two peaks followed by a valley” per cycle in healthy subjects, analogous to the PQRST waveform of an ECG. Remarkably, this furniture-based radar could discern subtle variations in the waveform. In tests with 8 young adults and 15 older adults, the system achieved heart rate estimates within 4.8% error (∼±1–2 BPM) and detected changes in the waveform shape associated with certain cardiac conditions. For instance, in subjects with prolonged QT syndrome (a condition predisposing to dangerous arrhythmias), the radar captured an extra third peak in the mechanical heartbeat signal (as opposed to the normal two peaks). All four subjects with prolonged QT in their study had normal heart rate and HRV by conventional measures, yet the contactless sensor revealed an abnormal pattern in their heartbeat mechanics. This suggests radar-based monitoring might detect certain cardiac dysfunctions earlier or noninvasively by analyzing the waveform morphology, not just rate. The “smart furniture” concept also highlights user convenience – the monitoring is invisible and embedded in daily life (just sit in your chair), addressing privacy and compliance by “monitoring in the background”.

Another notable development is the use of ultra-miniaturized radars in consumer electronics. Google’s Project Soli created a tiny 60 GHz radar chip (only 6.5×5×0.9 mm) originally for gesture sensing. Google then leveraged Soli for the Nest Hub (2nd gen) smart display to enable Sleep Sensing – a feature that tracks the user’s sleep duration, movements, breathing rate, and snoring without any wearable. In 2023, Google researchers published a study (Xu et al., Sci. Reports) validating the Nest Hub’s contactless heart rate detection during sleep and meditation. They collected data from 62 users (498 hours of sleep) and 114 users (over 1,100 minutes of meditation), comparing the radar’s heart rate readings to reference measurements. The Soli-based system achieved a mean absolute error of ~1.7 BPM for sleep and ~1.1 BPM for meditation – extremely accurate for a no-contact method. The recall (coverage of valid readings) was also high, indicating reliable tracking throughout the night. This work represents the first large-scale consumer application of radar vital-sign monitoring, essentially turning a bedside gadget into a health monitor. The Nest Hub can also derive respiratory rate and detect sleep disturbances (coughing, movement) using a combination of radar and audio sensing. Such products show that ambient vital sign monitoring is not confined to labs – it’s already reaching end-users, providing insights like “your respiratory rate was 14/min last night” or flagging possible sleep apnea events, all with just a device on the nightstand.

Clinical Applications and Evidence

Home Monitoring for Early Warnings

One of the most powerful use-cases of ambient RF monitoring is early detection of patient deterioration in home settings. Continuous tracking of trends in vital signs can alert caregivers to subtle changes. For example, a rising resting respiratory rate or heart rate could indicate an oncoming infection, heart failure exacerbation, or in extreme cases, an impending cardiac arrest. In the aforementioned MIT study on older adults with COVID-19, the elevated nocturnal breathing rate picked up by the Emerald device signaled a decline days before hospital transfer. Similarly, the Parkinson’s disease monitoring example shows how long-term changes in breathing patterns can indicate neurodegenerative progression, potentially allowing intervention or therapy adjustments earlier than periodic clinic visits. Researchers have noted that by the time symptoms are noticeable, a condition like PD or even cardiac arrhythmias may have been active for years – hence the value of passive nightly monitoring to catch issues in their “silent” phase.

Another acute scenario is suspected cardiac arrest: if a person collapses at home, a system that detects no breathing and no movement for a certain period could automatically call for help. While we did not find peer-reviewed trials explicitly for in-home cardiac arrest detection via RF, the technology inherently can sense the absence of vital signs. In fact, contactless sensors are already being explored for fall detection and to monitor if an elderly person is motionless on the floor. Combined with vital sign sensing, an Emerald-like device could potentially distinguish a quiet sleeping person from someone who has no pulse/breathing and trigger emergency response. Current research is focusing on reliability and reducing false alarms in such critical applications.

Importantly, clinical validation of home systems is underway. A 2024 evaluation by Ravindran et al. tested three commercial contactless monitors in the homes of 35 older adults (mean age ~71). They included a bedside radar (Somnofy) and two under-mattress BCG sensors, and compared all to gold-standard sleep laboratory measurements. All three devices showed good accuracy for heart rate (mean error <2.2 BPM) and breathing rate (error ≤1.6 breaths/min) when benchmarked against ECG and respiratory belts. Moreover, they could track changes across the night and even capture sleep apnea-related metrics. For instance, the Withings Sleep Analyzer’s snoring and apnea indices correlated well with clinical polysomnography (r²=0.76 for snore time, 0.59 for apnea-hypopnea index). The authors conclude that contactless bedroom sensors are “reliable for monitoring heart rate, breathing rate, and sleep apnea in older adults at scale,” enabling detection of acute changes in health and long-term trend analysis. In other words, even in populations with chronic illnesses and irregular sleep, these systems performed robustly – a promising sign for real-world deployment.

Hospital and Clinical Settings

In hospitals, the vision is that RF-based monitors could continuously watch patients without wires, improving comfort and enabling earlier intervention. Current ICU/ward monitors require electrode leads and cuffs that limit mobility and can cause skin breakdown or dislodgement. A contactless system could monitor a patient who is walking around the room or in the shower, etc., ensuring vital signs aren’t missed. This is especially valuable on general wards where nurses currently measure vitals only every few hours – a deterioration (like escalating breathing rate or arrhythmia) in between checks might go unnoticed until the next round. Ambient sensors fill that gap with continuous data. In fact, an FDA guidance in 2020 encouraged wider use of remote patient monitoring devices to manage hospital workloads, and we saw several pilots during COVID where wireless sensors were deployed in wards or field hospitals for this reason.

One specific area is neonatal and pediatric care. Babies in the neonatal ICU must be monitored closely, but their delicate skin makes adhesive electrodes and wired sensors problematic (they can cause skin injury or discomfort). Researchers are developing contactless radar monitors that can be placed near the incubator to track infant breathing and heart rate with no leads. A team in India (Hari et al.) published a 2025 protocol for a low-cost FMCW radar system aimed at monitoring neonatal breathing in the hospital and at home. Their goal is to detect apnea (cessation of breathing) in preterm infants by recognizing the slight chest movements via radar. This could alert staff the moment a baby needs stimulation or ventilation, and avoid false alarms from impedance-based apnea monitors. The authors report having a working prototype and plan to validate it against standard NICU monitors, anticipating that results will show comparable breathing rate accuracy with the advantage of being nonintrusive and safe for newborn skin. If successful, such radar devices could replace or supplement current neonatal vital sign leads, reducing discomfort for thousands of preemies.

Similarly, projects in Europe (Fraunhofer and others) are testing “medical radar” units in clinical settings to measure respiration and pulse of adult patients in bed, hoping to integrate them into hospital rooms as a continuous early-warning system. The concept of “Internet of Things” in healthcare includes smart hospital rooms with built-in sensors that constantly log vital signs and detect events like patient falls or cardiac arrest. Smart beds with pressure sensors and overhead Doppler sensors are also being studied.

Overall, while home deployments have led the charge (due to the strong value in chronic care and pandemic-driven remote monitoring), hospital adoption is on the horizon as the technology proves its reliability and obtains regulatory approval. Many recent studies report not only the feasibility of these devices but also their “comparable performance to clinical-grade” monitors. This suggests that in the near future, unobtrusive RF monitoring could become part of standard clinical practice, improving patient comfort and safety by continuously watching for early signs of distress (e.g. rising respiratory rate indicating sepsis, or lack of breathing indicating an arrest).

Conclusion and Outlook

In summary, ambient radio-frequency vital sign monitoring has evolved from clever lab demos into a mature technology now validated in peer-reviewed clinical studies. Using faint microwave signals, these systems can continuously and unobtrusively measure respiration, heart rate, and even heart motion patterns without any sensors on the body. The past five years in particular have seen an explosion of research translating this technology to real-world healthcare: from hospital trials of radar monitors for infants, to at-home monitoring of chronic diseases (Parkinson’s, sleep apnea), to large-scale demonstrations of arrhythmia detection (AF) and HRV tracking that rival medical-grade devices. Dina Katabi’s work laid the groundwork by proving vital signs could be sensed through walls, and now innovations like the Emerald device are actively being used to monitor patients remotely with success (e.g. catching early warning signs of COVID deterioration). Likewise, consumer adoption is underway via devices like Google’s radar-equipped Nest Hub, hinting that nightly vital sign monitoring may soon be as routine as sleep tracking on a smartwatch – but done passively, with nothing to wear.

Looking forward, these technologies have the potential to transform both home care and clinical monitoring. In the home, they enable a “safety net” for seniors and at-risk patients: the environment itself watches for falls, breathing cessations, or cardiac events and can summon help immediately. Subtle trends like a gradual increase in nighttime respiratory rate or a decline in gait speed can be detected and correlated with emerging health issues, allowing proactive interventions (for example, adjusting heart failure medications before a crisis, or detecting asymptomatic AF before a stroke occurs). In hospitals, contactless monitors could free patients from tethers, improving comfort and mobility while still keeping a vigilant eye on vitals. Early-warning scores could be calculated continuously, and alarms triggered for early signs of patient deterioration (tachypnea, bradycardia, etc.) hours before a code blue.

Of course, challenges remain – ensuring reliable performance in presence of motion artifacts, protecting privacy and data security, and integrating these data streams into clinical workflows. But the trajectory of research is very encouraging. As multiple studies reviewed above have shown, modern RF sensors can be accurate, robust, and clinically informative. They truly fulfill the vision of ambient intelligence in healthcare: the patient’s room (be it a bedroom or hospital ward) quietly monitors their well-being in the background, “sensing” trouble early on and enabling caregivers to respond in a timely manner. With ongoing clinical trials and growing real-world experience, ambient radio-wave vital sign monitors are poised to become a valuable tool for improving patient outcomes through early detection and unobtrusive continuous care.

References

- Adib F, et al. (2015). Vital-Radio: Using RF signals to monitor breathing and heart rate through walls.

- Zhang B-B, et al. (2024). Contactless HRV measurement using 60GHz radar. Nature Communications.

- Katabi D, et al. (2018). Emerald: AI-driven ambient sensing for healthcare.

- Zhang X, et al. (2021). Respiratory rate monitoring in COVID-19 recovery. Frontiers in Psychiatry.

- Yang H, et al. (2022). Diagnosing Parkinson’s via breathing patterns. Nature Medicine.

- Chen X, et al. (2025). AI-enabled radar for atrial fibrillation detection. Nature Communications.

- Gharamohammadi A, et al. (2025). Smart chair with radar-based cardiac waveform detection. Scientific Reports.

- Xu X, et al. (2023). Sleep sensing using Google Nest Hub’s radar. Scientific Reports.

- Ravindran A, et al. (2024). Validation of contactless bedside monitors. JMIR mHealth.

- Hari H, et al. (2025). Radar-based neonatal respiration monitoring: A protocol.

- Google. (2023). Nest Hub Sleep Sensing Documentation.

- MIT CSAIL. (2021). Emerald Innovations overview.

- Fraunhofer Institute. (2024). Medical radar sensors in hospital settings.

Leave a comment